The Problem with Pink

“Looks like pink is the new black!” Galveston County Jail made recent news headlines for switching from green uniforms for incarcerated persons to “safety pink uniforms.” This change was reportedly made to “discourage recidivism, enhance visibility for corrections officers in identifying potential threats, and create a calming atmosphere” with the department arguing that “the color pink is believed to help alleviate feelings of anger.” A quick look at the comment section would disabuse anyone from the notion that the switch was made because of the supposed calming nature of the color pink. One comment reads, “Sheriff Joe lives on! Nothing better than humiliation to change an attitude.”

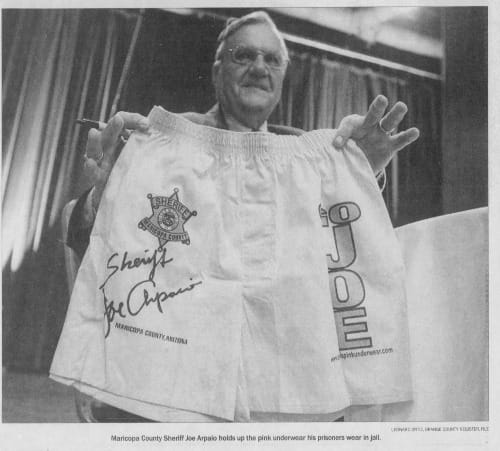

The comment references former sheriff Joe Arpaio who ran the infamous Tent City Jail with a philosophy emphasizing punishment, scarcity, and control. Under his reign, Joe Arpaio reintroduced chain gangs, erected tent-housing in excessive heat conditions for incarcerated people, and forced the incarcerated to wear pink underwear and other clothing. Since the 1990's, the practice has spread to numerous communities across the U.S. In 2015 Chief Gary Jones of Grovetown, Georgia was inspired by Joe Arpaio to implement not only the use of pink underwear but pink uniforms and even pink handcuffs, commenting “It’s our job to make sure they don’t want to come back.”

In their article, "Performing America's Toughest Sheriff: Media as Practice in Joe Arpaio's Old West" professors Chris Lukinbeal and Laura Sharp described the phenomenon of Joe Arpaio's "America's Toughest Sheriff" persona as a form of public theater, "This performative act of the lawman and the careful construction of the modern day Wild West in which it is situated are used to cover up practices of cruelty, racism, and corruption." These policies and practices are meant to send a message to the public that all is well because the "bad guys" are being humiliated and punished, thus crime is being discouraged and public safety improved.

Yet a study of the Maricopa County jail system as well as an official governmental review of the Tent City jail showed that Arpaio's policies did not improve recidivism rates. This makes sense, as humiliation and shame are not associated with positive social outcomes. Studies have found associations between humiliation and feelings of helplessness, antisocial behavior, as well as violence against oneself and/or others (suicide, assault, murder, and even terrorism) [1]. Dr. Evelin Lindner, a celebrated clinical psychologist and University of Oslo Professor of Psychology, describes humiliation as "the strongest force that creates rifts between people and breaks down relationships."

Furthermore, the gendered nature of the practice invokes misogyny and homophobia, where law enforcement weaponize a color associated with femininity to evoke feelings of emasculation among male incarcerated persons. Historically, pink uniforms have been associated with incarcerated women, not as punishment but as a reward. In the 1960's, those incarcerated in Tennessee's state prison for women could only wear pink if they were deemed as "model prisoners" by the administration. Otherwise, they would be forced to wear the stereotypical striped uniforms referred to as "disciplinary stripes." [2]

Professor Steven Nelson of the University of Houston's Department of Sociology, recently described this relationship in reference to the Galveston County jail, "This discourage recidivism part is an attempt to say, ‘oh look prison is so humiliating you don’t want to come back.’ So, they are doing little things to tweak masculinity of prisoners to embarrass them." In one study, an incarcerated man commented about the use of pink uniforms as an intentional challenge to their masculinity because it "degrades a grown man's dignity... it's not right trying to dress us like women."

When prison and jail administrators lean into making incarceration a traumatizing and demoralizing experience, there are significant consequences for the mental health of incarcerated people. In 2012, Eric Vogel, a 36-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia died of an acute heart attack while running from officers of the Maricopa Sheriff's department. Vogel had described to his family experiencing severe psychological trauma and sexual assault by Maricopa County sheriff's deputies only weeks before when he was detained under suspicion of committing a burglary. Although he had been "deemed in need of psychiatric care," four of Joe Arpaio's sheriff's deputies forcibly stripped him naked and forced him into one of the jail's pink uniforms. His family later cited this experience as the reason he was terrified of being detained again, thus leading to his acute physical and mental health crisis and subsequent death. An attorney for the family commented, "Pink underwear sounds funny until you have a paranoid schizophrenic who thinks he's being prepared to be raped." [3]

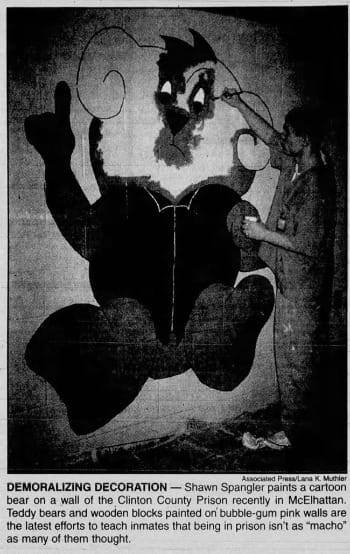

Other prison and jail administrators have taken the idea of gendered humiliation to even greater levels. Inspired by Joe Arpaio, a state prison in Clinton County, Pennsylvania not only began forcing incarcerated men to wear pink unforms, but also installed "toddler playroom decor" throughout the unit to create "sissy" rooms. Scowling teddy bears and baby blocks murals were added to walls meant not only to emasculate incarcerated men, but to also infantilize them. One journalist described the experience, "So when inmates enter the prison they spend their first hours in the pink intake area, looking at a gigantic, blue, smiling teddy bear wearing an appropriate, black-and-white-striped bow tie and holding a bouquet of balloons. Below the bear is a banner bearing the message, 'Punishment is Medicine'." [4]

Like Sheriff Jimmy Fullen of Galveston, Warden Tom Duran of the Clinton County state prison also described pink as a "calming color... good for soothing." Yet, he also made it clear the fundamental purpose of the policy was to humiliate incarcerated men, "We want them to be embarrassed... show them that it's a humiliating thing to be here." It is worthy of note, the incarcerated artist who painted at least one of the murals described learning to draw during periods spent in isolation (solitary confinement), having been incarcerated since he was just a boy of sixteen. [4]

The clothing that incarcerated people are forced to wear may seem like a marginal issue within the U.S. carceral system, but it represents an entry point to engage in broader discussions on why politicians and government officials embrace tough-on-crime policies. Sheriff Jimmy Fullen of the Galveston County Jail made the choice to implement the use of pink uniforms, drawing significant media attention. He has also been facing enormous public and professional scrutiny after being accused by The Texas Commission on Law Enforcement (TCOLE) of falsifying government documents, leading the agency to recommend his Texas peace officer's license be revoked. Among several allegations, he is accused of knowingly omitting details of his own early criminal history (several arrests--including for assault) in job applications and materials. After winning the election for Sheriff, Fullen filed a lawsuit against TCOLE arguing that his license cannot be revoked after being elected for the role. Fullen and TCOLE are currently in mediation.

Regardless of the intentions of people in places of power that champion humiliation and shame as a tool of punishment, we must be willing to engage with our own cultural beliefs that "punishment is medicine". Our beliefs relating to what people "deserve", especially for those who have harmed others, often create more harm than healing or safety. Practices that rely on humiliation as a deterrent, undermine the mental health of incarcerated people, and thus undermine public safety and make our communities less safe. The relationship to misogyny and gendered/sexual violence should also not be overlooked as contributors to harm and violence within carceral institutions and in communities. The U.S. has the highest rate of incarceration in the world with unbelievably high recidivism rates, and spends $182 billion annually maintaining systems of carceral infrastructure. Letting go of the false belief that harming the people who have caused harm is going to stop or prevent more harm is a necessary step in transforming our understanding of justice and how to create true safety in our communities.

- Li, et al. 2024. "Prevalence of experiencing public humiliation and its effects on victims’ mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis." Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 18:1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/18344909241252325

- Bowles, Billy. 1964. "Feminine Touch Adds Color to Prison Life." The Hartford Courant, December 28th, pg. 2.

- Adams, Guy. 2012. "Sheriff's Pink Prison Uniform Led to Inmate's Death, Rules US Court." The Independent, March 9th.

- Muthler, Lana K. 1996. "Miserable in Pink: Prison uses Toddler Decor, Pink Uniforms to Humiliate Inmates." The Press Enterprise, December 10th, p. 19.